1980s Japanese PC gaming has never really been as widely fetishised overseas as its console counterpart, which lent my first trip to Akihabara’s Beep a couple of years back the thrill of discovery. It’s my first encounter with so many of these games, though even if you’re a veteran of the scene you’re bound to be surprised by what’s in the doujin section, where you’ll find self-published efforts from hobbyists, often complete with self-penned covers. For all that, it’s a game I had heard of before - albeit dimly - which grabbed my heart.

Glimpsed running on a NEC PC-9801, A-Train 2 is the 1988 instalment of Artdink’s civic transport simulator looking both bewildering and bewitching: there’s a whole world going on inside that monitor, presented in crisp isometric view. I spend a couple of minutes pondering its menus and marvelling at all that teeming life implied within its pixels before moving on, but it’s stuck with me ever since. Just like the games I used to pore over in the pages of Mean Machines that I could never possibly afford, it’s something I’ll return to occasionally in the small arcade in my imagination where all the other games I’ve yet to play reside.

A-Train is a simulation series superficially similar in style to Sim City - indeed, its most high profile moment came when Maxis published A-Train 3 in the west - though it predates that series by four years, and its fundamentals are entirely different. In A-Train, your focus and primary form of interaction is through civic transport systems, your initial aim to piece together towns, laying tracks and positioning stations in order to see the map flourish and grow. It’s abstraction and efficiency, a thing of industry and polished excellence that’s also quick to the heart of why I’ve got such a soft spot for boom era Japan.

It is very much a product of the era. A-Train started life as the work of hobbyist programmer Tatsuo Nagahama, who founded Artdink to work on software with a band of fellow PC enthusiasts. The first prototype for A-Train was a simple hymn to the power of these machines, and the simple pleasure of laying out train tracks across a digital landscape like a child laying down tracks on their bedroom floor, but then the team realised it needed something more - and so the game grew around the edges of that simple pleasure, just as villages, towns and later cities blossom around the edges of the stations you lay down in response to your successes.

A lot has blossomed around the series’ foundations in the years since its inception, which makes finally getting to play an A-Train this past week a bewildering experience. “Badly designed, poorly presented, overly complicated and utterly tedious,” is how Ellie Gibson summed up 2008’s A-Train HX, the only other time we’ve covered the series here, and you could say pretty much exactly the same of the Switch’s A-Train: All Aboard! Tourism. It is a baffling, abstruse, horrifyingly dense thing, and yet it’s beautiful all the same - enough to see me spend a dozen hours pushing on through as I fail to wrap my head around it.

Part of that persistence is down to the fact it costs just north of £50 and I’m determined to extract some value from it, and part of it’s down to an admiration for any series that’s soldiered on so long with a sole developer at the helm. After 36 years plying its trade Artdink knows what it’s doing, and you can feel all that experience in the breadth of systems that support the old fundamentals of laying down lines of tracks.

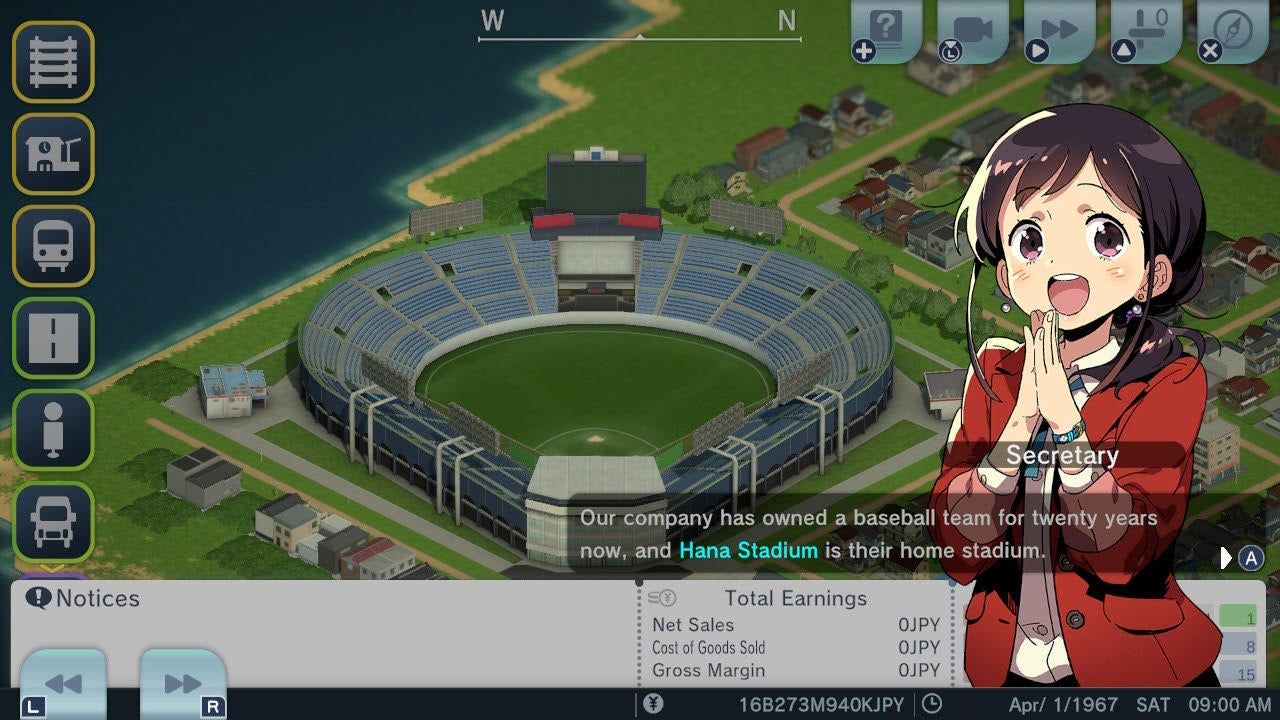

At its heart A-Train: All Aboard! Tourism is the same game - link together towns by laying down tracks and building stations, then see those towns grow - and it’s probably the most accessible it’s ever been. There are scenarios to play through - hold on to the company’s baseball team and get them to turn a profit! Increase foot-fall to the temple on the outskirts of town! - and advisers on-hand to help you achieve them. There’s even a tutorial mode of sorts that slowly folds in the myriad systems you’re able to manage. For all that I still struggle to comprehend so much of what’s essentially a hardcore accounting simulator, but I’ve rarely enjoyed being confused so much.

A-Train feels like the kind of game that exists regardless of the player, a petri dish you’re invited to prod and poke at yet one that will carry on without your input. It’s a living, breathing thing - and even if I don’t understand so many of its systems, I’ve got faith that after 36 years doing its thing Artdink has them refined and realistic, so I can just let them churn away and do their thing as I nose around the virtual world I’m tending. What a world it is, too - the iconic isometric view is retained, though with a flick of the stick you can use a free cam, or even head down to ground level and hitch a ride on one of your trains, seeing towns, cities and the fields in-between roll by.

For all the mundanity of a game that’s mostly about settling spreadsheets, A-Train possesses a magic shared with only the very best games. I can’t imagine I’ll ever fully understand it, just as I can’t imagine I’ll ever remove it from my Switch’s hard-drive, and as I imagine I’ll keep checking in on this perfect little computer world every once in a while. For all its faults, and its more than occasional fussiness, A-Train has managed something quite remarkable; it’s lived up to the promise of that strange little game I glimpsed on an old PC in an Akiba basement all those years back.