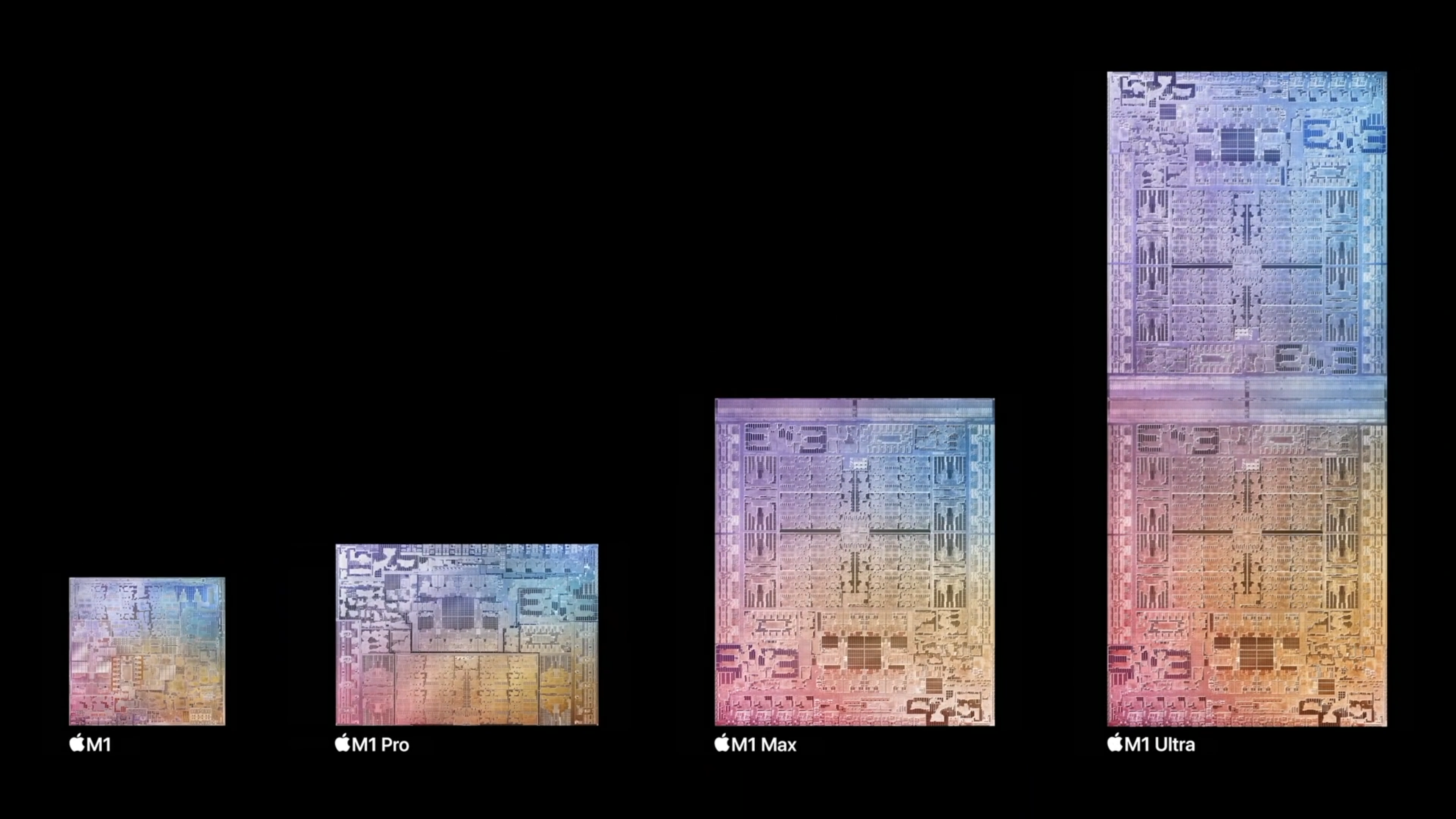

The M1 and M2 lines are the culmination of a long journey that has seen the firm transition away from SoCs based on third party design and IP, moving all chip design in-house to the furthest extent realistically possible. Apple designs its own GPUs, its own CPUs, and handles SoC design and integration. This results in tremendous control over processor design - the kind of control you would need to scale a phone processor up for high-end desktops. Which brings us to the M1 Ultra. Since 2020, Apple has been moving its Mac desktops and notebooks away from Intel CPUs and AMD GPUs and over to its in-house SOCs, taking the same fundamental tech from iPhones and integrating it into computers. Apple started with lower-end and lower-power form factors, but finally came around to high-end desktops with the release of the Ultra a few months ago. The M1 Ultra isn’t really its own unique chip, however. It’s actually two M1 Max SoCs connected over a high-bandwidth 2.5TB/s interposer. To the operating system and the user it seems like one monolithic chip with 1 CPU and GPU, but in reality this is two chips linked through a first-of-its-kind interconnect with the performance to support a dual-chip GPU and CPU. The Ultra packs a whopping 20 CPU cores, split between 16 performance cores and 4 efficiency cores in a configuration similar to modern Intel designs. While the clockspeeds may be lower than desktop PC CPUs, instructions-per-clock are higher on the performance cores, leading to similar overall performance-per-core. In its highest-end spec, the 21 teraflop GPU features 64 of Apple’s in-house graphics cores, with performance similar to an RTX 3090 according to Apple, though we’ll touch on this later. To round things out, the system packs a stunning 800GB/s of memory bandwidth to keep those GPU and CPU cores well-fed. M1 Ultra is only currently available in the Mac Studio desktop computer, which we tested in its maxed-out configuration, with 128GB of memory and an 8TB SSD. Most interestingly, this computer has a volume of just 3.7 litres, which is truly tiny and only slightly larger than an Xbox Series S. It uses two blower-style fans that pull air through a large copper heatsink to dissipate the roughly 200W that the system pulls at load, which is a small fraction of the energy used by a high-end desktop PC. So let’s move on and actually measure how fast this machine is. We’re going to start off with gaming tests before closing with productivity benchmarks and synthetics. Is this machine truly as fast as a high end desktop PC - or possibly even faster? Let’s take a look at our gaming benchmarks, calculated via video capture as is the Digital Foundry way. While internal benchmarks are largely accurate these days, our philosophy is that the only frames that matter are the frames that actually make it to the video output of the hardware. It’s not a particularly large table because, unfortunately, there aren’t many high-end Mac games that we can actually test, particularly when it comes to big-budget games. But we do have a few titles here - and the results are intriguing. For our gaming tests, we’ve got a 16 inch Macbook Pro with the fully-enabled M1 Max chip, our maxed-out Mac Studio, an MSI GP66 gaming laptop, with an eleventh-gen i9 and a 150W RTX 3080 mobile processor, and a high-end desktop PC with a Core i9 12900K paired with the mighty RTX 3090. Looking at Shadow of the Tomb Raider. This isn’t a native Apple Silicon game, as the title was written for x86, so the M1 chips here have to use the Rosetta 2 translation layer to function - but it doesn’t really seem like that has much of an impact on performance. The benchmark sequence running at max settings at 4K shows the 3080M and M1 Max are neck-and-neck, while the Ultra falls squarely between the M1 Max and the 3090. The Ultra has solid performance and reasonable scaling from the Max, but isn’t quite holding the line against ultra high-end GPUs. Metro Exodus - the original non-RT version - has a decent Mac port, although again it was written for x86. The Ultra splits the PCs here as well, while the Max does a good job of fending off the 3080M. On the flip side, there seem to be very serious problems with frame-times and stuttering when vsync is disabled for on Macs for some reason, which I noticed across these tests. Total War: Warhammer 3 is another x86 game, but it doesn’t seem to hold up quite as well as Metro or Tomb Raider. M1 Ultra is far behind the 3090 here and barely keeps pace with a high-end gaming laptop. Perhaps this can be chalked up to a sub-optimal port, or problems with the Rosetta translation. But what about native Apple Silicon games? There are remarkably few games for Apple Silicon, and most of them are iOS ports, not conventional PC software. There is one prominent game that we can test across platforms though - World of Warcraft. This is a full-bore Apple Silicon version of Blizzard’s long-running MMO, but despite running natively, the same pattern emerges with the M1 Ultra yet again falling squarely between the two PC systems, falling well short of the 3090 but still delivering performance in line with a high-end PC GPU. The Max is borderline unplayable while the 3080M hovers around 30fps. All of these systems would be perfectly fine with the game at remotely reasonable settings, of course - we are running the game essentially maxed out at a whopping 8K internal resolution to create a proper stress test. There’s one cross-platform game graphics benchmark that runs natively on Apple Silicon as well - 3DMark Wildlife Extreme, which renders a set of relatively simple 3D scenes at 4K. Here, the Ultra falls somewhat short of the 3090 but comes in a solid 76 percent faster than the Max. Ultimately, the Ultra seems to sit somewhere below the 3090 in graphics performance, at least as far as we can tell from benchmarking across operating systems. It’s still a powerful processor though and seems to slot in at roughly the 3070 or 3080 level depending on workload. Scaling from the M1 Max is reasonable, but not perfect. Typically, you should expect a 60-70 percent performance improvement over the single-chip option. Perhaps the interposer is causing some minor hiccups here, as using multiple chips for one GPU requires a massive amount of bandwidth. These results are really just for evaluating raw performance though, as the Mac is not a good gaming platform. Very few games actually end up on Mac and the ports are often low quality. If there is a future for Mac gaming it will probably be defined by “borrowing” games from other platforms, either through wrappers like Wine or through running iOS titles natively, which M1-based Macs are capable of. In the past, Macs could run games by installing Windows through Apple’s Bootcamp solution, but M1-based chips can’t boot natively into any flavour of Windows, not even Windows for ARM. As you’ve likely realised from the table above, I also spent some time benchmarking the CPU in the M1 Ultra. I tested Blender, Geekbench, Cinebench and Handbrake - and the Ultra’s results are compelling. We’ve swapped the GP66 for my desktop computer here, which packs a Core i9 10850K. Think of this as Core i9 10900K with a barely perceptible clock-speed reduction. Across these tests, the 12900K and M1 Ultra prove very comparable. The two chips are essentially a match with respect to multicore performance, though the ultra-high frequencies the 12900K is capable of can give it the edge in some single-threaded tests. The 10850K and M1 Max are closely matched as well. The scaling from M1 Max to M1 Ultra is close-to-linear across these runs, unlike our graphics benchmarks. On average, M1 Ultra is 88 percent faster, with some results approaching 100%. Linking up two clusters of cores across an inter-chip medium is something we’ve seen in the PC space for years now and very good scaling is to be expected here. Finally, I thought I’d throw in some real-world benchmarks from a couple of programs I frequently use - Final Cut Pro and Topaz Video Enhance AI. We’re looking at the two M1 computers here, as well as a 16 inch 2019 MacBook Pro with an eight-core Intel CPU and an AMD RDNA 1-based GPU. The results are very curious in Final Cut. While both M1 machines trounce the Intel-based MacBook, export times are virtually identical across the M1s. So what’s going on? With typical Final Cut workloads on M1 chips, export performance seems to be dictated by the hardware video encoders. The M1 Ultra has the same video hardware encoders as the Max, so there’s no meaningful performance difference when encoding a ProRes or h.264 video without many effects. To actually see a difference in export times, you’d need to really stress the GPU with lots of effects and Motion templates. Even then it would be hard to see a large difference. That isn’t to say that there aren’t big moment-to-moment performance differences, though - Final Cut generates video thumbnails in real-time on the CPU cores, which occurs nearly instantly on an M1 Ultra and is significantly slower on M1 Max. In general, the timeline is more responsive and the editing process is more fluid - but that won’t be reflected in simple export tests. Topaz AI is much more straightforward. We’re strictly GPU-bound here and the M1 Ultra shows a solid performance improvement - completing the test 43% faster - though not particularly impressive given the doubling of GPU hardware. Both machines crush the 2019 MacBook Pro, as expected. So, the M1 Ultra packs similar performance to the highest-end PC chips, trading blows across a variety of metrics. CPU performance is up there with the best Intel has to offer, while the GPU sits one or two rungs beneath the PC performance leaders at the moment. The key metric with M1 Ultra isn’t raw performance, however, though it is largely competitive with PCs on that front. It’s power consumption. The Ultra manages to pull even with fast consumer desktops while consuming one quarter to one third of the power consumption. The Mac Studio itself only pulls about 200W when fully loaded, and usually draws much less. So, why is the M1 Ultra so much more efficient than comparable PC designs? Firstly, Apple has a considerable process node advantage over its competitors. By leveraging TSMC’s 5nm process, Apple is one or two silicon fabrication nodes ahead of its nearest rivals at the moment, which means higher density and lower power consumption for Apple’s chips. Apple generally gets access to TSMC’s newest processes before its PC competitors and has been producing chips at 5nm for over two years at this point. Secondly, Apple is simply throwing way more silicon at the problem. The M1 Ultra uses a whopping 114 billion transistors across two chips; in contrast, the GA102 GPU in the RTX 3090 packs just 28 billion transistors. With so much more logic, Apple can run its chips at lower clocks and lower voltages and still achieve similar performance. The extremely high density of TSMC 5nm helps a lot here. Lastly, Apple’s CPU and GPU architectures play a significant role here. These are designs that are primarily designed for iPhones and other low-power applications. There are likely many mechanisms inside the chip to keep energy consumption in check, including very effective power gating. Given the immense potential of the Apple solution, there’s one final question that’s worth addressing: would a move to ARM be practical for the broader PC market as well? After all, Apple achieved an enormous performance improvement when they moved to ARM, so could this be a good solution for PC vendors too? Generally the answer is no, at least not at the moment. There are two major problems here. The things that make Apple’s designs effective aren’t specific to the ARM instruction set license they use. These are mostly factors we’ve discussed already - its unique high-performance architectures and process node advantage being the most important. Critically, no-one else is currently offering an ARM CPU core design capable of going toe-to-toe with AMD and Intel. The second problem is the lack of an effective translation layer for x86 code. MacOS has Rosetta 2, which is a relatively efficient and broadly compatible solution for running x86 code seamlessly on ARM-based Macs. Windows 11 for ARM has a software emulator for x86 programs, but performance is degraded and compatibility is lacking. The M1 Ultra is an extremely impressive processor. It delivers CPU and GPU performance in line with high-end PCs, packs a first-of-its-kind silicon interposer, consumes very little power, and fits into a truly tiny chassis. There’s simply nothing else like it. For users already in the Mac ecosystem, this is a great buy if you have demanding workflows. While the Mac Studio is expensive, it is less costly than Apple’s old Pro-branded desktops - the Mac Pro and iMac Pro - which packed expensive Xeon processors and ECC RAM. Final Cut, Photoshop, Apple Motion, Handbrake - pretty much everything I use on a daily basis runs very nicely on this machine. For PC users, however, I don’t think this particular Apple system should be particularly tempting. While CPU performance is in line with the best from Intel and AMD, GPU performance is somewhat less compelling. Plus, new CPUs and GPUs are incoming in the next few months that should cement the performance advantage of top-end PC systems. That said, the M1 Ultra is a one-of-a-kind solution. You won’t find this kind of raw performance in a computer this small anywhere else. Gaming on Mac has historically been quite problematic and that remains the case right now - native ports are thin on the ground and when older titles such as No Man’s Sky and Resident Evil Village are mooted for conversion, it’s much more of a big deal than it really should be. Perhaps it’s the expense of Apple hardware, perhaps it’s the size of the addressable audience or maybe gaming isn’t a primary use-case for these machines, but there’s still the sense that outside of the mobile space (where it is dominant), gaming isn’t where it should be - Steam Deck has shown that compatibility layers can work and ultimately, perhaps that’s the route forward. Still, M1 Max and especially M1 Ultra are certainly very capable hardware and it’ll be fascinating to see how gaming evolves on the Apple platform going forward.